Updated on September 4, 2019

Day 1 of Carolinas Vacation, Battlefields of Yorktown

It was end of May and beginning of summer, and I decided my adventures should go a little bit farther than usual, and there came this trip to the Carolinas.

So on the afternoon of May 30th, I went to New Jersey to pick up a dear friend and very good companion for the trip, and we set off for Norfolk, Virginia the next morning. It was 4pm by the time we drove past Yorktown, as we decided that

- We would be driving into rush hour traffic of Norfolk, which would be bad.

- I had been driving for hours that day without any sightseeing, which would be boring.

Since Yorktown Colonial National Historical Park was just nearby (actually I could see the spire of Victory Monument as I crossed York River), we decided to pay it a visit.

Finding a parting spot was easier than what I expected, even on the popular Yorktown Beach (and it’s free).

Coleman Memorial Bridge and Beaches of YorktownActually these beaches were a popular weekend getaway for the local.

Yorktown, Virginia was the site of the siege and subsequent surrender of British General Charles Cornwallis to General George Washington and the French Fleet, which marked a decisive victory in the American Revolutionary War. This NPS website provided more details of Yorktown’s history before the Revolutionary War.

Right next to our parking lot was the cave that Cornwallis used as headquarters during the siege, where he sought shelter from intense Union bombardment.

Cave as British HeadquarterI did feel bad for the British as their commander was reduced to such primitive working conditions.

An Archer House

Yorktown had a “great fire” in 1814. This destroyed all but the foundations of this house, thought to be one of Thomas Archer’s “Houses under the Hill”. The present restoration is the nineteenth century dwelling built on the older stone foundations.From official information board.

After that, we headed uphill for the visitor center that’s about to close.

Victory MonumentIt took then Continental Congress 10 days to decide to build this memorial, but almost 100 years to actually break ground.

Click for detail of Victory Monument

“Resolved, That… Congress… will cause to be erected at York, in Virginia, a marble column, adorned with emblems of the alliance between the United States and his Most Christian Majesty; and inscribed with a succinct narrative of the surrender of Earl Cornwallis to his excellency General George Washington… to his excellency the Count de Rochambeau… and his excellency the Count de Grasse….” Journals of Congress, October 29, 1781

Just 10 days after the victory at. Yorktown, the Continental Congress directed a monument be built to commemorate the siege and the American-French alliance. However, funds were not legislated to its construction, until 1880, as the centennial anniversary of the battle approached.

A congressional committee of legislators from the original 13 colonies delegated oversight of the project to the Secretary of War, who in turn, chose architects, Richard M. Hunt and Henry Van. Brunt, and sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward to design the new monument. The country’s spirit of reconciliation in the aftermath of the Civil War affected the design, as evidenced by the inscription, “One Country, One Constitution, One Destiny” on the monument’s shaft.

On October 18, 1881, the cornerstone for the monument was dedicated during events commemorating the 100th anniversary of the siege.

On the night of July 29, 1942, lightning decapitated the Statue of Liberty and destroyed her arms. The damaged statue was replaced with a redesigned statue 15 years later.From official information board.

There’s a small museum in the visitor center, which didn’t take long to visit. Outside the visitor center, huge chunks of lands where battle once raged were preserved (I didn’t know this before). Pamphlets about recommended driving routes were also provided in the visitor center.

Lord Cornwallis’s Campaign Table

Click for details

According to records connected with this campaign table, it is thought to have belonged to Lord Cornwallis during his time in Yorktown. The table has a top and a base and breaks down for transporting. The top is composed of a legume panel with a rosewood border. The folding trestle legs are made of padauk. All these woods are tropical and generally used for furniture. .Campaign furniture, design to be folded up, packed, and carried on the march, has been used by travelling armies since the time of Julius Caesar, and even earlier. ..The table can be set at two different heights. Although not visible, each leg is marked with a brass upholstery nail numbering from one dot to four dots which corresponds with those on the table top corners.

General Washington’s Dinning Marquee

General Washington’s Dinning Marquee

Click for detail

The headquarters were under canvass during the siege of and after the surrender of Yorktown.

George Washington Parke Custis, 1843

As commander of the allied forces at Yorktown, Washington met the challenges of a complex military operation. At his headquarters, in counsel with the French commander, the Comte de Rochambeau, and other allied officers, Washington made crucial decisions that led to the victory.

Washington conferred with staff, received visitors and dined with up to 40 people at a time in the dining marquee.

… there are only three major generals here, I have two days’ duty going into or leaving trenches, and even on the third day I scarely get to headquarters (from which the expresses leave), while General Washington spends almost all of his time, supervising the progress of our works.

Marquis de Lafayette to Chevalier de La Luzerne,

Camp Before York, October 12, 1781

From official information board.

When the museum and visitor center closed at 5, we began our walking tour of historic Yorktown.

TownhouseThis one was closest to Victory Monument, I guess it was occupied by some not-so-important figures during the Revolution and thus had remained a townhouse ever since.

And then, occasionally information boards along the street told of the significance of some nearby buildings that otherwise looked rather inconspicuous.

Click for detail about Dudley Digges House

“… Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton directed them to charge into the town, [Charlottesville, Virginia]… and to apprehend, if possible, the governor and assembly. Seven members of the assembly were secured.. . and several officers and men, were killed, wounded, or taken.” Lieutenant-Colonel Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781

Dudley Digges built this classic Virginia Tidewater style home around 1760. The outbuildings, wellhouse, kitchen, granary, and smokehouse are typical of those found in the colonial era. The house was restored in 1960 and the outbuildings reconstructed by the National Park Service in the 1970s.

One of the members of the Virginia assembly captured by the British during their Charlottesville raid on June 4, 1781 was the former lieutenant governor of the state, Dudley Digges. Digges’s capture ended his prominent political involvement in the American Revolution.

The Digges family had participated in colonial government since the immigration in 1650 of Dudley’s great-grandfather; Edward Digges, from England. Dudley was born around 1728 and by his early twenties was a practicing lawyer in York County. He served in the House of Burgesses from 1752 until the start of the American Revolutionary War. Throughout the war, Dudley remained active in numerous areas of Virginia government, including helping to write the commonwealth’s first constitution and becoming one of the first members of the state council.

Dudley’s home, like so many other Yorktown houses, was damaged during the 1781 siege and rendered uninhabitable. Dudley moved to Williamsburg and died there in 1790.

From official information board.

Click for detail about Nelson House

“General Nelson… was excelled by no man in the generosity of his nature, in the nobleness of his sentiments, in the purity of his Revolutionary principles, and in the exalted patriotism that answered every service and sacrifice that his country might need.” James Madison, 1789

One of the few tangible reminders of Thomas Nelson’s sacrifice for independence is his home, which still bears scars from Allied cannon fire during the 1781 siege.

Nelson’s grandfather, Thomas, built the house around 1730. The Nelson family retained ownership of the house until 1908. In 1968, the National Park Service purchased the house and restored it to its 18th century appearance.

On September 25, 1781, Governor Thomas Nelson, Jr. wrote Lord Cornwallis asking that citizens of Yorktown be permitted to return to town to move out their belongings. Three days later, the American and French armies reached Yorktown and the siege began.

In the 18th century there were six outbuildings on the northwest side of the Nelson House. By the early 1900s, only the chimney from the kitchen remained.

Thomas Nelson, Jr.’s legacy is a lasting example of a life dedicated to independence for his country.

His support towards political freedom from Great Britain began while a member of Virginias’ colonial legislature. In addition to protesting British taxes and leading Yorktown’s tea party, patterned after the one in Boston, he was one of Virginia’s delegates to the Continental Congress.

In May 1776, he advocated that Virginia officially support independence, a proposal that helped lead to the Declaration of Independence signed by Nelson and 55 others. Nelson continued to support the revolution through political channels and used his own funds to purchase military supplies. On June 12, 1781, he was elected the third governor of Virginia and faced the greatest challenge of his public career, the invasion of the British army.

As governor and general of his state’s militia, Nelson participated in the victory at Yorktown. One day after the British surrendered, Governor Thomas Nelson, Jr. wrote to the Continental Congress: “…the whole loss sustained by the Enemy… must be between 6 & 7000 men. This Blow, I think, must be a decisive one.”

In November 1781, Nelson resigned as governor, poor in health and in debt., He died on January 4, 1789, and was buried next to his father and grandfather at Grace Church just one block from his home.

From official information board.

See also www.nps.gov/york/learn/historyculture/nelson-house.htm

TownhouseJust next to Nelson’s house was this house looking historic too. But since it’s not associated with any important figures, the cunning owner was free to add some expansion to its back (see photo on left).

TownhouseJust next to Nelson’s house was this house looking historic too. But since it’s not associated with any important figures, the cunning owner was free to add some expansion to its back (see photo on left).

Across the street from these two buildings was “Great Valley”, what’s now a footpath connecting downtown Yorktown to its beaches. Wild flowers were blossoming beautifully over the land.

Click for detail about Great Valley

“I desired you not to send the Things you used annually send me… I…. shall not import any more necessaries till the hateful Acts are repealed. The Ministry promised to get a Repeal of that imposing the Duties on Glass

Paper & Colours; But, tell Them in plain English, That alone Won’t satisfy America…” William Nelson to merchant, Mr. John Norton in London, November 18, 1769

Before the American Revolution, this narrow footpath, cutting through the Great Valley, was a major thoroughfare that linked Yorktown’s busy waterfront district with businesses and government offices on Main Street.

At. the head of the Valley were the Nelson stores, started sometime in the first decade of the 1700s by English immigrant, Thomas Nelson. Nelson’s merchant business thrived at this location, and richly supported three generations of the Nelson family until the eve of the American Revolutionary War. William Nelson, who inherited his father’s business, supported the efforts to repeal British taxes on imports. In 1776, four years after his death, his sons, Thomas and Hugh, were forced to close the family business due to the war.

Declining tobacco yields and the 1781 siege crippled Yorktown’s economy. In 1814, a fire destroyed the waterfront district and some buildings on Main Street, including the Nelson stores. The town never recovered and fell into a quiet existence.

From official information board.

Click for detail about Cole Digges House

“I hope your Lord will think fit to move His Majesty to appoint another Councilor… I humbly recommend to your Lord for that Purpose Mr. Cole Digges a Gentleman who lives very convenient to the Seat of Government, of an ample Fortune, good Parts & a fair Character…”

Governor Alexander Spotswood to the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations, February 24, 1718

On September 15, 1720, Cole Digges of Yorktown was sworn in as a member of the royal governor’s council, a powerful and prestigious political position in the colonial government that he held for 24 years. Digges’ wealth, his position as a representative in the colonial legislature and his apparent support of the royal governor, Alexander

Spotswood, combined to make him an attractive candidate for the council. Digges’ success came at a time when Yorktown was reaching its zenith, and the colony was still loyal to Great Britain.

Cole Digges was born in 1691, the same year Yorktown was established. His family’s wealth came primarily from producing a well known brand of “sweet scented” tobacco, called “E.Dees”, named after his grandfather, Edward Digges. As Yorktown slowly grew into a prominent tobacco port, Cole Digges, only in his early 20s, became a merchant, purchasing a town lot in 1713. As the town prospered, so did Digges’ enterprises. At his death in 1744, he owned two plantations, this house, a warehouse, store house, wharf and other lots in Yorktown.

Cole Digges witnessed the expansion of Yorktown from its early beginnings to a thriving community. His son Dudley Digges, whose home is one block east on Main Street, saw the town decline.

Thomas Pate

In 1699, ferryman Thomas Pate purchased this town lot and constructed his home here. The house was sold twice before Cole Digges acquired the property in 1713. Originally thought to be Pate’s house, research and the building’s architectural details indicate that the house was constructed around 1720, when Cole Digges owned the property. The interior of the house represents the colonial revival style of 1925.

“…an example of all that was fine and most lasting in Colonial domestic architecture…” Clyde F. Trudell, 1938

Throughout its long history, the Cole Digges House served many roles in the village of Yorktown. Originally used as a residence and warehouse, in later years it was a teahouse/store and the First National Bank of Yorktown.

In 1921, Mrs. Helen Paul of Michigan bought the building and four years later began a major remodeling project transforming the 200-year old building into its current appearance by applying the Colonial Revival style made popular at Colonial Williamsburg and reflected in original and reconstructed buildings along Main Street, including Swan Tavern, the Medical Shop, and the Nelson House. Colonial Revival elements include red brick, side lights at doorways, paneled or louvered wood shutters, and multi-sash windows. John H. Scarf, the architect who developed the plans for the building, stated that the “intention of this restoration [is] to preserve the spirit of an early Eighteenth Century cottage in all details.”

There were major changes to the exterior and interior, including raising the first floor seven inches, altering the north end chimney to provide a window opening on the second floor, installing an entry to the basement from Read Street, adding wood paneling on the first floor walls, and adding a skylight in the stairwell. Slate replaced the wood shingles to protect the building from catching fire and “to give the appearance of an older roof.”

In 1968, the National Park Service acquired the building. Plans to repair the failing building included retaining the slate roof. However, the slate roof was replaced with wood shingles in 1978. In 2011, a simulated slate roof replaced the wood shingles, allowing for a more durable material and an appearance that more closely resembles the building’s Colonial Revival restoration.

From official information board.

Cole Digges HouseNow a cafe shop, probably because the house had changed hands too many times and there’s nothing that historic about it, so there’s this redevelopment opportunity.

Click for detail about Custom House

“… collectors are hereby impowered to demand, secure, and receive all… the duties, customes and imposts… with full power to go on board any boat, ship or other vessel, or into any house… where he shall have just cause to suspect any fraud… collectors… shall… in April and October… render a true and just account upon oath, and make payment… of money as they… shall receive and collect for the duties….” An Act for Ports &c., April 16, 1691, Virginia Legislative Assembly

In 1691, Virginia’s colonial legislature passed “An Act for Ports”, in an effort to better regulate trade for the collection of import and export fees and duties. The act called for the creation of several ports, including Yorktown, and the appointment of Collectors of Ports by the royal governor. During Yorktown’s peak as a commercial port in the mid-1700s, Richard Arnb1er and later his son, Jacquelin, served as collector of ports.

In 1721, Richard Ambler built this large, brick storehouse and from here he and his son handled their collector duties. Ship captains recently arriving and merchants arranging for transport of goods would convene at Ambler’s storehouse to complete the required paperwork and pay the assessed fees.

The outbreak of the American Revolution brought an end to many port activities, including the collection of customs. In 1776, Virginia militia troops were using the Custom House for barracks and two years later, Jacquelin Ambler sold the property.

In 1924, the Comte de Grasse Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution purchased the Custom House and restored it five years later. Today the Custom House still continues in use as a Chapter House and Museum.

From official information board.

Click for detail about Grace Church

“The pews and windows of the Church all broke & destroyed. The church was used as a magazine.” York County Records, Claims for Loses of York County Citizens in the British Invasion, Claim No. 31, 1783.

Grace Church, a religious centerpiece in Yorktown’s history, has endured two wars, a devastating fire, and at times, the crumbling of “old age”, while continuing to serve as a place of worship for over 300 years.

Constructed about 1697 for the York Parish of the Anglican Church, the official Church of England, the church was an integral part of the colonial community. Citizens were required to regularly attend services or fare criminal prosecution. Additionally, religious events such as weddings, funerals, confirmations and Sunday services provided people with social opportunities.

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, Virginia’s Anglican churches lost their government support. The churches struggled to survive while reorganizing as Protestant Episcopal Church in Virginia. The Yorktown congregation had additional challenges because the town’s population had decreased over 60% as a result of the war.

The resiliency of the congregation was tested again in 1814 when a fire destroyed the church’s roof and interior. For the next 34 years worship services were held in various locations, including the courthouse and the Nelson House. In 1847, Bishop John Johns wrote, “The stone walls of the old Church…are still standing. It is proposed to use them, in part, to provide a suitable place for our services.” By the fall of 1848, the church had been rebuilt, utilizing the original walls. It became known as Grace Church for the first time.

Today the congregation of Grace Church remains active in the Yorktown community, while the building continues to offer a link to Yorktown’s colonial past.

From official information board.

Site of Home of Nicolas Martiau

And about this Nicolas Martiau’s home site, it was a residential unit with no NPS information board signifying its importance. Only a plate put in place by either its owner or some non-profit was telling the story about this adventurer. There’s just too much history around Yorktown.

After that, we got back to the car and started our driving tour of the battlefield.

There wasn’t too much to see near the First Siege Line, so without getting out of car we headed straight to Second Siege Line next.

By the way the Second Siege Line was also next to Yorktown National Cemetery, where bodies of Confederate soldiers from the Civil War was buried. We paid it a visit first.

Bivouac of the Dead BoardSort of surprised to see coins left on the board, some of which must have seen quite some age. I always thought this only happened in Asia.

After that, we did a brief tour of the trenches.

FieldsJust in front of the tree line were redoubts from Britain, as this narrow piece of land used to separate two waring nations.

After that, we visited Redoubt 9 and 10, the last two strongholds of British defense.

Click for detail about Redoubt 9 and 10

“The… Batteries were principally directed against… the enemys advanced redoubts on their extreme… left to prepare them for the intended assault…” General George Washington’s Diary, October 14, 1781. ,

The completion of the Allied Second Siege Line was blocked by a portion of the British outer works-two, detached earthen forts, called Redoubts 9 and 10, located 400 yards in advance of the British Inner Defense Line. Though General Washington considered allied frontal attacks against the British Inner Defense Line impractical and costly, Redoubts 9 and 10 were a different matter. General Washington called upon the infantry to capture these positions.

On October 14, Allied artillery Bombarded Redoubts 9 and 10 most of the day, preparing for American and French assaults. At approximately eight o’clock in the evening, the artillery briefly fell silent. Then several cannons fired in unison, the signal for the attack columns to move on their objectives.

The column marched in silence, with guns unloaded, and in good order: Many, no doubt, thinking that less than one quarter of a mile would finish the journey of life…

Captain Stephen Olney, Rhode Island Regiment

The Marquis de Lafayette selected the light infantry companies from his Continental Army division to carry outs the American attack on Redoubt 10. Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Hamilton led the assaulting force of 400 Americans against the 70 British defenders.

Concerned an accidental musket firing would give away their advance, the light infantry approached the redoubt. with unloaded weapons. The British discovered the attack column as it neared the redoubt and vigorously defended their position. The Americans surged through the abatis obstructions surrounding the redoubt, then through holes in the palisaded log walls within the trench, breached the top of the redoubt, and within 10 minutes of mostly hand-to-hand combat, secured their objective.

Alexander Hamilton, in his report to Lafayette on the action, noted that the British were “intitled to the acknowledgement of an honorable defence.”

“Last evening the enemy carried my two advanced redoubts on the left by storm, and during the night have included them in their second parallel… My situation now becomes very critical…”

General Charles Lord Cornwallis to General Sir Henry Clinton, October 15, 1781.

From official information board.

Reconstructions of Redoubt 10This was partly reconstructed where fragment of its moat was found in 1956. The remainder of it, as well as parts of adjacent works, was washed away to sea during the 175 years of crumbling river banks.

Reconstructions of Redoubt 10This was partly reconstructed where fragment of its moat was found in 1956. The remainder of it, as well as parts of adjacent works, was washed away to sea during the 175 years of crumbling river banks.

I remembered it was quiet and peaceful on the battlefield that day, with smoothing breeze and fragrance of sprouting green, all the opposite of the intense battle these lands witnessed centuries ago. It’s great that sons and daughters of this land cherished this hard-fought serenity.

Next stop on the tour route was Moore House, where parties signed the surrender treaty. Road to Moore House passes through some dense forest and steep ravine, which was also the approach road used by the American to reach siege lines from their encampments farther back.

Reconstructed First Siege LineWashington’s troops built works like these when they open the Siege of Yorktown. These fortifications, together with those of the French, made a circling line that stretched a mile and a quarter, from the York River to Yorktown Creek.

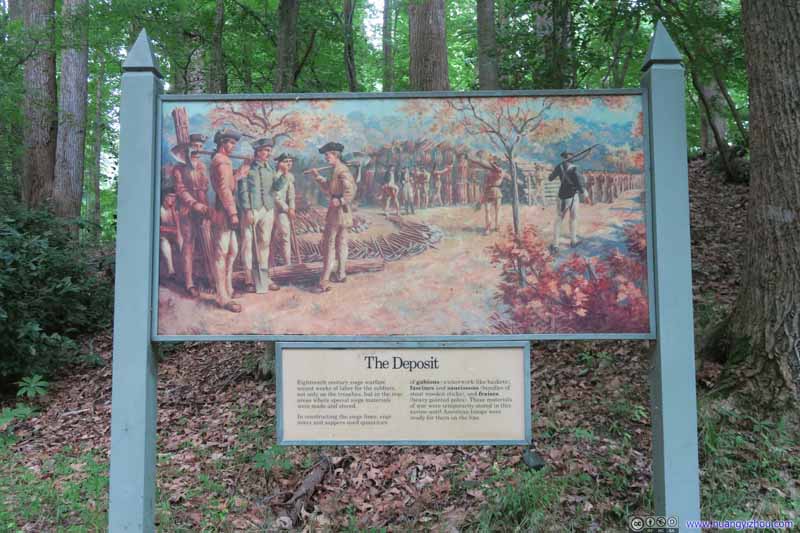

The DepositEighteenth century siege warfare meant weeks of labor for the soldiers, not only on the trenches, but in the rear areas where special siege materials were made and stored… In constructing the siege lines, engineers and sappers used quantities of gabions (wickerwork-like baskets), fascines and saucissons (bundles of stout wooden sticks), and fraises(heavy pointed poles). These materials of war were temporarily stored in this ravine until American troops were ready for them on the line..

Click for detail about Moore House

“I propose a cessation of hostilities for twenty four hours, and that two officers may be appointed by each side, to meet at Mr. Moore’s house, to settle terms for the surrender of the posts of York and Gloucester.”

General Charles Lord Cornwallis to General George Washington, October 17, 1781

On October 18, 1781, after over eight days of continual bombardment, the battlefield was finally tranquil. Washington and Cornwallis now focused on the surrender negotiations taking place at this house, the home of Augustine Moore. Each general had selected two officers to handle the face-to-face discussions. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Dundas and Major Alexander Ross represented the British, while Lieutenant Colonel John Laurens and Second Colonel Viscount de Noailles spoke for the Allies.

Slowing the process was Laurens’s insistence, with Washington’s support, that the British submit to similar terms granted by the British to the defeated American army at Charleston. South Carolina, in 1780: Those terms had deprived the American soldiers to surrender with the army’s personal honor intact. The British argued for better terms, but the Allies prevailed and around midnight, a draft of the “Articles of Capitulation” was completed with 14 provisions, including two conditions that denied the British the “full honors of war”. These two articles required that at the surrender ceremony, the British army would case their regimental flags, and their military band would play British music instead of professionally saluting the victor with American and French songs.

History of Moore House

The Moore House is an early 18th century home that has undergone many structural changes and about 50 owners. The house was extensively damaged during the Civil War, both by cannon fire and soldiers stripping wood from the house or campfire use. By the 150th anniversary of the surrender, the house was in a dilapidated state. In 1931, the National Park Service undertook its first restoration of a historic building-the Moore House. Three years later the project was complete, and the house once again appeared as it did in 1781.

From official information board.

See also www.nps.gov/york/learn/historyculture/moore-house.htm

Probably because of Moore House’s remote location where land was plentiful, the House had a huge backyard where nowadays trees grew beyond the chimneys of the house itself. Also, the outbuildings had better survived than the more important houses of downtown Yorktown. Unfortunately, the doors of Moore House was still locked.

As for the surrender treaty, I thought at first it should be simple as waving white flags, but it turned out the parties were going through intense negotiations over seemingly trivial matters, like what music to play during the ceremony.

Next stop on the tour route would be grounds where surrender ceremony took place.

Dam over Wormley CreekThe earth dam in front creates Wormley Pond which existed in 1781 when Augustine Moore operated a grist mill here. American troops marched over the dam regularly as they moved to and from the Siege Line

American Field Hospital Site

Click for detail

I attended at the hospital, amputated a man’s arm, and assisted in dressing a number of wounds.

Dr. James Thacher, October 1781

Dr. James Craik and General George Washington met in 1755 during the French and Indian War, forming a life-long friendship. Dr. Craik was Washington’s primary physician and was at his bedside when he died.

I hastened with all speed to the hospital… to procure another supply from Dr. Craik; and he desired that if the Marquis de la Fayette should be wounded, I would devote to him my first attention.

Dr. James Thacher, October 7, 1781

Dr. James Craik, chief physician and surgeon, supervised the American Field Hospital located in this area. Assisted by Drs. James Thacher and Aeneas Munson, he fought a constant battle to protect soldiers from exposure to small pox and other diseases, to secure adequate medical supplies, and to shelter the sick and wounded. Patients needing long term medical care were transported to the American hospital in Williamsburg.

This field hospital, located in the vicinity of the Marquis de Lafayette’s headquarters, may reflect the concern Dr. Crail had for Lafayette’s welfare.

From official information board.

Surrender Field

Click for detail

On the 17th, at about to o’clock, the British raised a white flag on their walls, beat a parley on their drums, and the firing ceased on all sides. Then the terms of surrender were agreed on between Washington and Cornwallis, and on the afternoon of the 19th the British army marched out on the main road and surrendered prisoners of war.

Asa Redington, 1st New Hampshire Regiment

On October 19, 1781, British troops, commanded by Lieutenant General Charles Lord Cornwallis, marched from heavily damaged Yorktown and surrendered on this field to the allied French and American armies under the command of General George Washington. Cornwallis, pleading illness, did not accompany his men.

From official information board.

From Google Maps, the actual surrender field was vast, fitting for the thousands of British troops that marched to their defeat. Part of the primary tour route (red) runs parallel to the surrender field, but we decided at this moment to take the secondary tour route (yellow) to encampments of American and French troops instead.

Baron Von Steuben Headquarter SiteThis general was experienced in siege warfare such as characterized the Yorktown battle and so he was invaluable to Washington. Von Steuben maintained headquarters here with his division of American troops..

However, the secondary tour route didn’t turn out to be as exciting as the primary one, with much fewer relics than information boards. So we cut it short and called it a day.

Beaver Dam CreekWe were sort of surprised to see trees here so lifeless.

Beaver Dam CreekWe were sort of surprised to see trees here so lifeless.

This sluggish and marsh headwater of the Warwick River generally divided the French and American encampments. Although both forces were under Washington, separate unit organization was respected and preserved through the siege.

Water CrossingTo and from Washington’s headquarters there was this water crossing, which could be problematic for cars with the low ground clearance, like mine.

French CemeteryThis simple cross is thought to mark the burial place about 50 unidentified French soldiers killed during the Siege of Yorktown.

END

![]() Day 1 of Carolinas Vacation, Battlefields of Yorktown by Huang's Site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Day 1 of Carolinas Vacation, Battlefields of Yorktown by Huang's Site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.