Updated on September 3, 2019

Day 5 of Carolinas Vacation, Charleston Day 2

Our second and last day of touring the historic city of Charleston South Carolina. We had to reach Columbia South Carolina for our overnight lodge, so today we would be visiting Fort Sumter, the place where Civil War started, and then be on our way to Columbia. So much for the historic buildings in downtown Charleston.

Liberty Square, where tour boats to Fort Sumter departed, was just a 20-minute stroll from our downtown hotel, passing streets full of history. It’s a Tuesday morning, but the quiet streets felt nothing like that of a major city.

Instead, it’s like a small town that artists would be drawn to.

Street ArtI guess the point of this art was either that in such a historic city life’s slow-paced, like crocodile on land, or that swamps were so ubiquitous in the south that people were indifferent to crocodiles?

Fort Sumter

We made it onto the first tour boat that departed at 9:30am. We did find there’s plenty of walk-in tickets available that day, thus we didn’t pay the evil one-dollar-or-something fee that TripAdvisor (which weirdly was what the boat tour website would direct one to make reservations) charged for online reservations.

At the very first, I would mistaken Castle Pinckney for Fort Sumter. Later when I could tell their difference, I thought, okay Castle Pinckney was so well located, that the first shots of Civil War must be fired from here. Neither were true.

At first I thought this cross must be in memory of soldiers of the Civil War. A Google search later it seemed that it’s placed by some real estate developer “in the name of his Bible study group”. Anyway, I will consider that some sort of art.

Reference:www.goupstate.com/article/NC/20030415/News/605154649/SJ/

Short story of Battle of Fort Sumter. South Carolina seceded from Union in December 1860. A few days later, Union Major Robert Anderson moved his small command from the vulnerable Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island to Fort Sumter, a more defendable location. Confederates saw this as a threat and began bombarding Fort Sumter in April 1861 from Fort Johnson which was the first shots of the Civil War. After 34 hours Major Anderson surrendered and evacuated the Fort to the Confederates. Towards the end of Civil War, Union Army continuously bombarded the Fort for almost two years until the Confederate Army abandoned it in 1865.

One interesting fact, by the time Union Major Anderson occupied the Fort in 1860, the Fort had been under construction for more than 30 years but was yet “unfinished”. Just a sign of the ineffectiveness of construction in the States.

Shell Embedded in Wall

Click for detail

A close look at this wall reveals Union artillery shells embedded in the brick. They were fired during one of the longest sieges in U.S. military history.

Batteries on Morris Island, about one mile South, and guns on Union warships shelled this Confederate stronghold for 22 months during 1863-1865. The bombardment, primarily from Morris Island, destroyed the gorge wall behind and severely damaged the left face wall here.

The bullet-shaped shells embedded here were fired from powerful rifled cannon. Rifling (cutting spiral grooves in the cannon’s bore gave a spin to the shell, increasing accuracy, range, and destructive power. Rifled shells could be larger and heavier than the old, round shot fired from smoothbore cannon.

From official information board.

Click for detail about these cannons

A disciplined, well-trained crew of five men could fire an accurate shot in less than one minute. Teamwork and timing during battle were essential to the crew of this 42-pounder smoothbore cannon, one of 27 guns that occupied these first-tier casemates.

This casemate is an 1870 reconstruction, but the cannon, which rests on a 1961 reconstructed carriage, is one of Fort Sumter’s original guns.

From official information board.

Restored Cannon

Click for detail

Not far from here stands a rifled and banded columbiad cannon mounted as a mortar (aimed upward, not like this photo). It is mounted like the gun being inspected by a South Carolina delegation after the evacuation of Fort Sumter by Union troops in April 1861.

The dependable columbiad, a heavy-barreled seacoast gun introduced in 1811, was used throughout the Civil War. Columbiads were not designed as mortars, but Federals mounted five of them here for that purpose in 1861. This 10-inch columbiad could fire a 128-pound shell on a high arc. During the Confederate bombardment, Union troops in Fort Sumter aimed their columbiad mortars at Charleston, but never fired them.

During the Civil War many columbiads, like this one, were “rifled” (spiral grooves cut in the barrel) and “banded” (a thick, metal band wrapped around the barrel base).

From official information board.

The post by this cannon looked very much like that Fort Sumter was selling naming rights to individual cannons. How American was this!

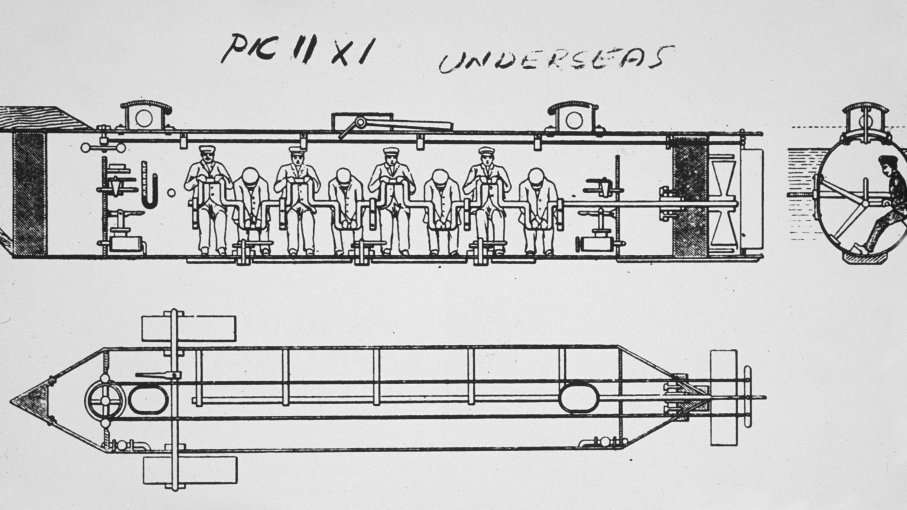

And then there’s a post telling the interesting story of a submarine powered by manual labor.

Click for detail about H.L. Hunley

On the night of February 17, 1864, the H.L. Hunley set out from Sullivan’s Island with a torpedo attached to a seventeen-foot spar to its bow. The target was the USS Housatonic, anchored four miles offshore. A Union lookout spied the suspicious object moving toward the ship and sounded an alarm. But before the ship could move away an explosion ripped through the Housatonic’s wooden hull and it quickly sank.

The H.L. Hunley disappeared after sinking the Housatonic. After searching for 131 years, in May 1995 the submarine was finally found 1,000 feet seaward of the Housatonic. The H.L. Hunley returned home on August 8, 2000, when it was recovered from a watery grave.

H.L. Hunley was 40 feet long with a crew of 8 men. The submarine’s sleek design helped it glide through the Water up to 4 knots. The air supply was limited. Once the candle went out the crew quickly returned to the surface for fresh air.

The earlier accidents and the final sinking resulted in the death of 21 men who volunteered on this experimental “peripatetic coffin.”

From official information board.

Click for detail about Union Bombardment of Fort Sumter

On July 18, 1863, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, a black regiment, led the direct assault on Fort Wagner, a Confederate stronghold near Morris Island’s north end. Under intense fire, the 54th briefly gained Wagner’s parapet, but fell back with heavy loss. Though the assault failed, it proved the courage of black troops and confirmed their military value for the Union. The Union then changed tactics, subjecting Fort Wagner to a two-month siege. The Confederates finally evacuated, abandoning Morris Island on September 6, 1863. Union gunners then aimed powerful rifled cannon at Fort Sumter. In the next two years, massive bombardments reduced most of Fort Sumter to rubble. Ironically, the more they damaged the walls the stronger they became. Slaves piled the debris into huge breastworks, twenty feet thick, and reinforced them with cotton bales, sandbags, and other material, rendering the fort impregnable to artillery.

In 1863-64 Confederates still held most of the strategic positions around Charleston Harbor. The Union Navy failed to take Fort Sumter by sea, and in June 1862 the Army failed against Secessionville, south of Charleston. Controlling Morris Island in 1863 enabled the Union to bombard Fort Sumter and Charleston.

From official information board.

Click for detail about Union Bombardment of Charleston

In 1861 the port of Charleston prospered. Keeping the city open to trade was crucial for Confederate survival. Confederate forts in Charleston Harbor – including Fort Sumter – protected Charleston throughout the war despite Union blockade, warship attack, and two years of bombardment and siege.

Despite military conflict in the harbor, relative peace prevailed in the city until 1863, when Union forces captured nearby Morris Island and mounted an eight-inch Parrott rifle called the Swamp Angel. This huge gun fired 150-pound shells and was aimed at the city of Charleston five miles away. The Swamp Angel’s first shot at 1:30 a.m. on August 22, 1863 caused panic in Charleston. This deliberate bombardment of a civilian population shattered the city’s security. The Swamp Angel’s brief career ended abruptly the following day when the overcharged gun burst while firing its 36th round. Other guns soon took its place, and the bombardment of Charleston continued intermittently for the next 18 months.

While bombarding the city was a strategic decision, many Union supporters believed Charleston deserved to be destroyed for leading the secessionist movement and firing the first shots of the Civil War. The Union bombardment, along with a devastating fire in 1861 and other fires set by evacuating Confederate forces in February 1865, destroyed much of the lower city.

From official information board.

Then there’s a post of Star of the West, which is a Union supply ship that, if not for outdated guns from the Confederates would be the target of civil war’s true first shots in January 1861.

Click for detail about Star of the West

Morris Island was the scene of the Civil War’s first hostile cannon fire, preceding even the bombardment of Fort Sumter.

By January 1861, Union troops occupying Fart Sumter were surrounded by Southern defenses. To reinforce Sumter, President James Buchanan secretly sent the unarmed coastal steamer Star of the West to Charleston. But news of the mission arrived first, and when Star of the West appeared, a South Carolina battery opened fire from Morris Island. Their outdated guns did little damage, but when the powerful guns of Fort Moultrie fired, Star of the West retreated, abandoning the mission.

Star of the West carried two hundred men, provisions. Small arms and ammunition. Hoping to avoid arousing Southern anger, President Buchanan sent the sidewheeler instead of a warship.

From official information board.

Click for detail about Union’s Night Attack

This corner of the fort was the site of the only attempt by Union forces to storm Fort Sumter during the Civil War.

On the night of September 8, 1863 a Union tugboat towed 500 sailors and marines in small boats to within 400 yards of Fort Sumter, then cast them loose to assault the fort. But the Confederates expected the attack. As the leading boats landed, the defenders opened fire, hurling grenades and bricks down upon the assailants. Guns of Fort Moultrie and the Confederate gunboat Chicora opened fire. The remaining boats retreated, and 124 Union men stranded here were killed, wounded, or captured.

For the next sixteen months, Union forces continued to bombard Fort Sumter, but never attempted another landing.

From official information board.

Sullivan’s Island and Lighthouse

Click for detail

Confederate control of Fort Sumter, Fort Moultrie, and supporting fortifications kept Charleston Harbor open despite the blockade by Union ships.

The main ship channel is in this photo, between Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie, within range of their powerful guns. Confederates built floating booms of timber and rope between the two forts, placed mines in the channel, and drove pilings into the channel bottom. Friendly ships could pass through a narrow opening in the barrier.

A barrel torpedo, a buoyant contact mine constructed of a barrel and wooden cones, could carry 120 pounds of powder. Floating unseen just below the surface, torpedoes were the most dreaded of all new weapons. Collision with a mine could sink an ironclad, thus throughout the war, union ironclads patrolled near the forts but would not venture into the channel.

The Union Navy blockaded Charleston Harbor from 1861-65, but blockade runners continued to slip in and out, carrying cargo crucial to the economic and military survival of the South. Using neutral ports like Bermuda and Nassau, blockade runners brought food, medicine, weapons, ammunition, and manufactured goods from Europe. They left primarily with cotton, but also carried diplomats, dispatches, and various products and valuables.

The risk of capture or sinking by Union warships was great, but so were the rewards. One voyage could bring a profit of $100,000. Despite the blockade, seventy-five percent of the runs were successful. They were often painted gray to blend with the sea and fog. Rainy weather and dark, moonless nights were ideal for a run into port.

From official information board.

Since we were the first group to land on Fort Sumter that day, park officials held a flag-rising ceremony and they tried to make it as solemn as possible, by a group of volunteers to unfold, hang and rise the flag in a most delicate way.

Flags were flying at half-staff in memory of the victims at Virginia Beach that day. Unfortunately, that solemnity was spoiled at the last moment when they overshot the halfway point of the flag and had to roll back.

Location of Battery Huger

Click for detail about Battery Hunger

Battery Huger, the black, concrete structure filling the center of Fort Sumter, was built in 1899 in response to the Spanish-American War. Named for Revolutionary War hero Isaac Huger, the battery was part of a seacoast defense system that protected Charleston Harbor. A gun crew could load and fire a 1000-pound shell every 90 seconds. The battery could hit a moving battleship eight miles away. By 1945 installations like Battery Huger were obsolete, and Fort Sumter was transferred to the National Park Service.

From official information board.

Click for detail about Gorge Wall

Fort Sumter was designed with its strength toward the sea. The gorge, the lightly-armed rear wall facing inland, was vulnerable to attack from Morris Island. Early shelling left the gorge wall in ruins. Continued bombardment reduced the gorge to rubble, but Confederate soldiers and slaves reinforced the debris with sandbags and cotton bales, creating an earth work that made the fort stronger than ever.

The gorge wall originally contained offices, the guard house, storerooms, the powder magazine, and three-story apartments for officers and their families.

From official information board.

Also on the island was a small museum, which we took a brief tour before getting on the return boat.

Location of Fort JohnsonWhere the first shot of civil war towards Fort Sumter was fired. Unfortunately, the buildings in this photo were mostly later developments, with only a small hut being all that’s left of Fort Johnson by Google Maps, which was hidden somewhere behind the trees.

Walking Tour to Hotel

After that we went back to our hotel to retrieve my car, while padding the streets of Charleston for one last time.

Just by our hotel, we came across St Mary’s Catholic Church. Incorporated in 1791, it’s the first Roman Catholic parish in the Carolinas and Georgia. While its exterior didn’t look as magnificent as the city’s other more prominent churches like St. Michael’s, it did come to us as a delicate church with nice paintings. And it blended perfectly in the city streets.

Just across the street was another Jewish Church, Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim. Unfortunately the church door was closed to the public at that moment.

Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim Entrance

Click for detail about Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim

Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (Holy Congregation House of God)

Founded 1750

The cradle of Reform Judaism in the United States, 1824

Jews who settled in Charleston as early as 1695 worshipped informally until the founding of this congregation in 1750. First synagogue on this site, 1780-1792, was a converted cotton gin. A second built 1793, was burned in 1838. The Sunday School begun in 1838 was the second Jewish Sunday School in the United States. The present synagogue, designed by C.L. Warner and built by David Lopez, 1840, is the second oldest in the United States, and oldest in continuous use. The tabernacle was built in 1948 on the site of the old tabernacle (1838-1948). George Washington wrote the congregation in 1790: “May the same temporal and eternal blessings which you implore for me, rest upon your congregations.”

From official information board.

After that, we headed out of Charleston into James Island, where we visited McLeod Plantation.

McLeod Plantation

This would be the first plantation that I had ever visited. The guided tour it offered put more emphasis on enslaved people than the plantation owners.

During the Civil War, the McLeod’s fled the property, and the procession of the plantation changed hands between Confederate and Union armies. Our guide did mentioned that the McLeod’s had some difficulty regaining procession of the plantation after the civil war, which didn’t happen until 1870.

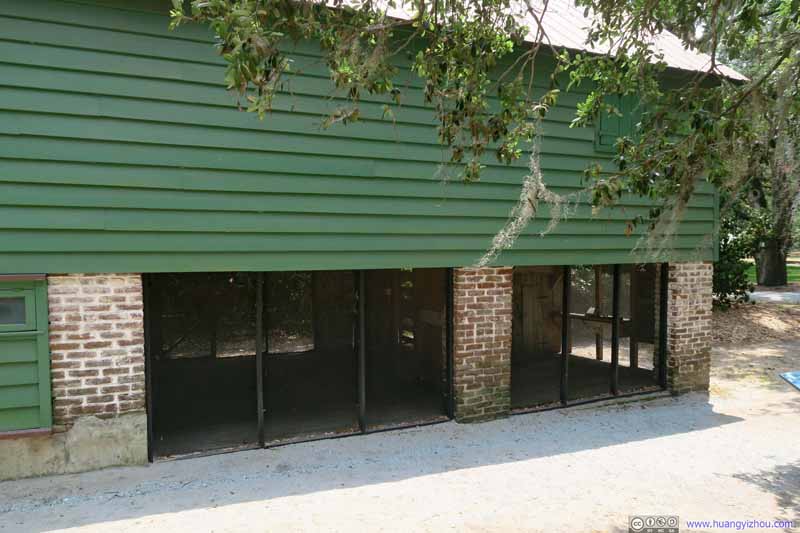

The Gin House was probably where our guide spent most of her time on. Apart from the predictable hideousness of forced labor, our guide did tell us there were forced sex, where plantation owners would pick the strongest male and force them to have sex with (often underage) female, hoping to have the best, most powerful offspring for them to sell at a good price. And like animals, the babies were taken away from parents immediately after birth, to the new buyer’s plantation. Sounds horrid.

And she did tell another interesting fact, that the price of a young, male (most expensive type) slave, adjusted for inflation, roughly equals a couple tens of thousands of today’s money, which was “almost enough to pay for her tuition”.

Click for detail the task system for slaves

Unique to the Lowcountry, this labor system assigned specific allocations of work, whether planting or growing cotton, Once completed, time often remained to pursue personal interests. Following emancipation this system persisted in the form of “two-day” contracts requiring freed people to work two days for plantation owners, leaving five days for themselves.

Imagine McLeod Plantation at its peak in 1860. It is a cold January morning and preparation for planting in March has begun. Low-burning fires stretch across the fields, fueled by last season’s shriveled stalks.

In this gin house last fall’s harvest, dried and cleaned, is fed into the gin to separate long delicate fibers from small black seeds. Towering bags stuffed with the world’s finest cotton await shipment to feed the insatiable demand of Britain’s textile industry. People slave to complete assigned backbreaking tasks under threat of the lash.

From official information board.

Old Entrance RoadThe McLeod’s strategically placed many of their slave cabins along this road, so their guests would see this sign of wealth on their way in.

Of the many slave cabins that used to stand on this land, only six remained today and were located on this avenue which’s called “transition row” nowadays. Some of the rooms were open for visit. Another surprising fact of the plantation, until 1990, which was the time the last of McLeod family passed away and the property be given to some charity, some of these rooms were actually rented out at “sub 20 dollar per month”. And that’s why there were some modern amenities like power outlets in these rooms.

Our tour also emphasized on the challenges former slaves faced after emancipation, many of whom knew working in plantation under some owner as their only way of life. As a result, many of the former slaves returned to the plantations they used to work at, and continued their old job under a different name, maybe “contract workers”?

Just to let people nowadays experience the labor intensiveness of cotton planting and harvesting, McLeod Plantation designated a small patch of land and invited volunteers from nearby towns to plant cotton. As our tour guide remembered, the first year they had enormous amounts of people showing up, the next year they only had a handful few.

There were also some exhibitions in the main house and visitor center. It was some turbulent times, not only to the slaves, but maybe to a less extent to the plantation owners, as they struggled to keep the plantation afloat in times of changing economy. Besides cotton, the McLeod’s attempted different plants like corn, but the plantation had been struggling ever since. The story of the McLeod’s in the 20th Century was basically like, selling or leasing off land to keep the plantation alive. Today, the historic site was only 9.2 acres in area, compared with 60+ at its peak.

Parts of McLeod Plantation was across the road from the main house by Wappoo Creek. On map it said there’s a cemetery for the former slaves, but it must be so well hidden that we didn’t find it.

Click for detail McLeod Plantation’s location

Hidden from Union gunboats, this place was essential to Confederates. Its secluded and protected location up a small creek shielded troop movements on and of James Island. The closest landing to railroad supply lines, it housed quartermaster stores and an ordnance depot. McLeod Plantation is one of the few antebellum sites on James Island to avoid destruction because of its strategic importance.

Until roads and bridges were built for automobiles, Wappoo Creek was a gateway rather than a barrier to the outside world. Its proximity to Charleston provided ready access for exporting the McLeods’ cotton and importing supplies and luxuries afforded by the planters’ lifestyle. It was from here that the Gullah, while enslaved and after emancipation, transported their produce and seafood to markets.

Wappoo Creek allowed the enslaved to visit – often without permission – family and friends separated by the local slave trade. Only after the shift to an automobile culture did Wappoo Creek impede movement of African Americans for activities like attending segregated schools.

From official information board.

Angel Oak

Before setting off for Columbia we took another detour and visited Angel Oak Tree on Johns Island, which was a 400-to-500-year-old giant tree with long winding branches.

Looking at these twisted branches that sometimes hid underground, I was reminded, in a not-so-good way, the tree-like mutation boss of House of the Dead III.

After that, we headed out for Columbia, South Carolina while having lunch/dinner along the way. Since it’s still early in the day (by our standards) and we won’t have too much to do tomorrow, we decided to stop by Congaree National Park.

Congaree National Park

Unfortunately, as we were approaching Congaree National Park we were hit by a thunderstorm. The good news was that, since the National Park was close enough to the city of Columbia, a T-Mobile user like me could still use internet to check out radar maps. It turned out that storm would soon be passing us, so with a little bit of patience at the Park’s parking lot, we were on our way exploring nature.

As for the park, it preserves the largest tract of old growth bottomland hardwood forest left in the United States by Wikipedia. For us, the useful information was that it has one 4km loop trail that’s on boardwalk, so that we didn’t have to set foot onto the muddy ground.

These cypress knees were probably the most unique sight of the park. At first I thought these were smaller, individual trees, but it turned out that they were structure forming above the roots of a cypress tree, either to provide oxygen to the roots, or to anchor the tree in soft soil, or maybe both.

Unfortunately, it was close to dusk and all the bugs in the forest seemed to be at their most active hours of the day. And they spotted, and, unlike most other bugs, followed an ideal prey, which was me (and weirdly, not my friend). So for the most part of the hike, I was swaying my arms all over the place trying futilely to rid the bugs. Extra workout.

It wasn’t a very long hike, and on boardwalk (which wasn’t usually the case in the States) and level ground it didn’t take much effort. Apart from the annoying bugs, forest air just after rain was bliss. However, watching cypress trees (and only cypress trees) for an hour might be somewhat boring, that’s probably why there’s only a handful of cars in the parking lot that afternoon.

After that, it was just a short drive to our hotel in the outskirts of Columbia, and we called it a day.

END

![]() Day 5 of Carolinas Vacation, Charleston Day 2 by Huang's Site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Day 5 of Carolinas Vacation, Charleston Day 2 by Huang's Site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

“Flags were flying at half-staff in memory of the victims at Virginia Beach that day. Unfortunately, that solemnity was spoiled at the last moment when they overshot the halfway point of the flag and had to roll back.”

It is customary when putting a flag up at half staff to raise it to the top then bring it down to half. When taking it down at sunset you have to raise it back up to the top then bring it all the way down. 🙂